I have recently taken to shooting infrared photos while I am out on photo excursions. The motivation for me is that, if I can easily and inexpensively produce a different type of photo from what I normally shoot, all the while not affecting my ability to shoot traditional color photos, then why not give it a try. The upside is that I might produce a few more quality, interesting images. The downside is that if the effort may be an abject failure, but if it does not cost me much in time or money then the risk is acceptable.

For instance, while I was tooling around the Bishop Creek watershed photographing fall colors, I took along my Panasonic Lumix LX3 that has been converted to shoot true infrared. What this means is that I can whip this tiny but high quality camera out of my pocket and blast off some infrared shots spontaneously. Infrared photography using external infrared-pass filters on a conventional digital camera typically requires long exposure times and a tripod, making for cumbersome shooting. However, if the camera is modified internally to allow only infrared light to reach the sensor, then long exposure times are no longer required, and one can shoot infrared photos handheld. This really makes having an infrared camera along sensible and productive. Several companies exist to perform these modifications, and they are reasonably inexpensive. Plus, you can always have them convert the camera back to visible light again (for a fee) if you don’t like the results. Probably the most popular cameras for infrared conversation right now are the Canon G9/G10 (and soon to be G11) line, but I prefer the wider angle of the Lumix LX3 so I bought a second one and had it infrared-converted. This particular image comes from the Table Mountain area, when the late afternoon sun was dropping behind the cliffs, leaving much of the hillside in shadow but the aspens in side light.

Aspen trees in fall, eastern Sierra fall colors, autumn.

Image ID: 23320

Species: Aspen, Populus tremuloides

Location: Bishop Creek Canyon, Sierra Nevada Mountains

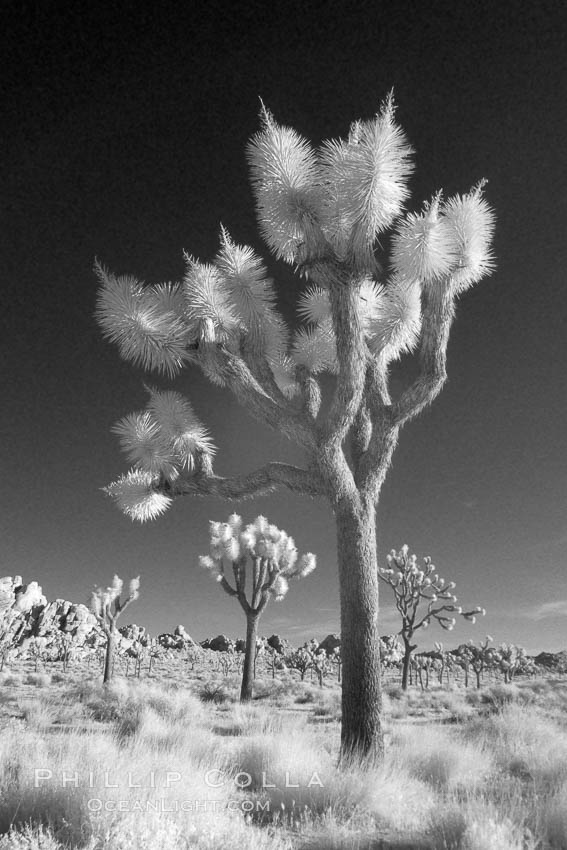

Here is another example I was quite happy with, a single Joshua Tree framed against a deep black, cloud-free, mid-morning sky. In this case, having an infrared camera along allowed me to shoot longer than I would normally have done. The light in Joshua Tree is really only good for about 30-60 minutes after sunrise, beyond that it is too harsh to shoot good images. However, the harsher and stronger the light becomes, the greater the amount of infrared light that is reflected by certain subjects such as plants. For this reason, infrared photography is usually at its best — in midday — when visible light photography is often at its worst. The two compliment one another well.

Joshua tree, sunrise, infrared.

Image ID: 22888

Species: Joshua tree, Yucca brevifolia

Location: Joshua Tree National Park, California, USA

I’m pretty happy with my little infrared-converted LX3 and its ability to shoot quick and reasonably high-quality infrared images. (Not to mention that we love our regular LX3 for snapshots and family photos.) However, I should mention there are some limitations to shooting infrared this way. The optics of todays digital cameras are designed for visible light, in particular, the wavelengths of light in the visible spectrum and how they pass through lens glass-air and glass-glass interfaces. Infrared light passes through the lens and into the sensor in a somewhat different way than visible spectrum light. I have found that this manifests in images that are softer than one would expect with visible light, and are sometimes prone to a vague “hot-spot” in the center of the image. The hot-spot seems to be in the blue color channel only, in my experience with the LX3, and only presents when the lens is at its widest angle (24mm-equivalent). By zooming in even a little bit, the hot-spot issue is alleviated. From the information I have read on some of the internet infrared photography websites, I think other cameras may exhibit both of these issues (soft focus, hot spots) as well but I am not sure as I have only used the LX3 in infrared. I believe the hot spot is a property of the camera sensor and the angle at which the light reaches the sensor, while the soft focus (most notably corner softness) is a characteristic of the optics and their transmission of light (infrared) in wavelengths quite different from those for which the lens was designed (visible). Usually I pull out either the red or green color channel to produce a black-and-white image, so the hot spot in the blue channel is not a great problem, but in those images in which I think I want the blue channel I just zoom in a little and all seems to be well. Also, the hotspot is not present in all images, it seems to have something to do with the direction of the sun and how intensely the subjects in the center of the image are reflecting infrared. Image softness is a property of infrared photography in general, and seems to me to be ameliorated somewhat by the strong contrast that infrared images typically have. In other words, the strong black-white contrast of an infrared image seems to more than make up for the soft detail, when the image is viewed as a whole.

Like this? Here are more infrared photos.

Keywords: infrared, joshua tree, yucca brevifolia, aspen, populus tremuloides.